As a medical student, I took a journey from data science (MS, 2017) to statistics (PhD, 2023). Below, I list some lessons learned.

Moving through worlds:

As a data scientist, I sometimes felt statistics depended on too many assumptions, and that prediction was a different task. This belief dissipated when I moved from the data science institute to the statistics department.

As a statistician, I sometimes felt that data science techniques were less interesting, as they did not usually involve inference. This belief dissipated as well.

In both data science and statistics, I felt like data science sometimes contained new names for concepts in statistics. This belief has persevered.

Compared with data science, statistics is more known to the general public. Statistical terminology allows an audience to anchor to healthy skepticism as well as genuine hope and expectations. Sometimes data science terminology is more intuitive (and exciting), but it is less often linked to genuine expectations.

I found data science to be very integrated into the team-based, community-driven culture of computer science, which was a great influence on me.

I did not have much formal background in statistics before starting in data science. In general, data science is welcoming to those with non-traditional backgrounds.

Communication and terminology:

I learned to always take time to communicate my research as clearly as possible. Doing so would deepen the work.1 The deeper the work, the more the distinction between data science and statistics fell away for me.

As I learned more about statistical terminology and the associated methods, I found that I could interact with existing statistical work. There is a lot of it—I sometimes found entire subfields of statistics devoted to topics that were only briefly touched upon during my training in data science.

When working with non-statistician, medical collaborators, I found that sometimes I had a subconscious desire to hide behind math, but that this must be overcome in order to do what is best for the patient.

A plug for probability:

Topics like sensitivity and specificity of medical tests connect to topics like neural networks through concepts in probability. I would recommend that one study probability to better understand any of these topics.

On statistics, machine learning, estimation, and inference:

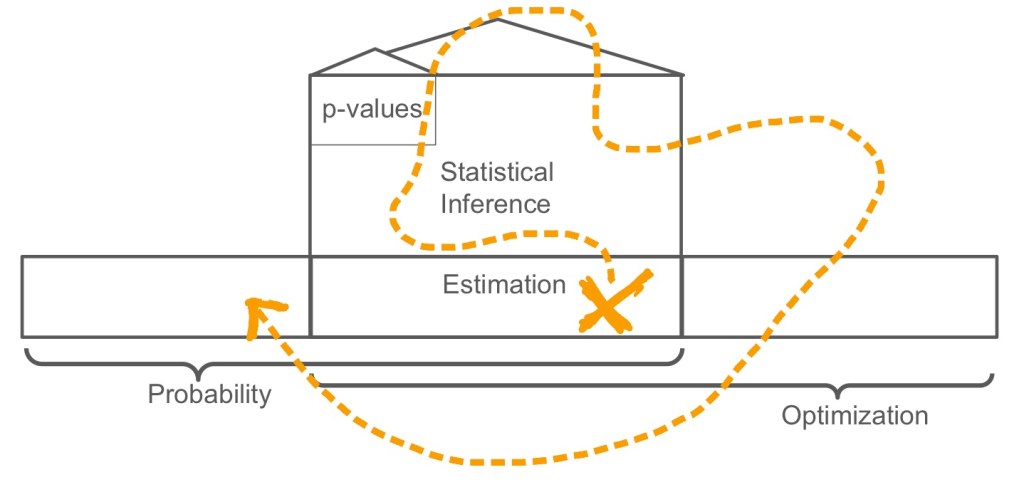

Statistical estimation is also known as machine learning, and both are fundamentally applications of optimization.

Statistical inference, which is meant to characterize the uncertainty of estimators, is a mathematical skyscraper built on top of estimation.

Statistical tests, which are often mischaracterized as “simple” are often highly sophisticated under the hood, based on hundreds of years of mathematical development.

Take care, you can get lost within the mathematics of inference, and you might miss other interesting estimation problems, like those having to do with text, images, or who knows what’s next.

Although neural networks are powerful, whether you use a logistic regression or neural network to estimate is often not a huge distinction. Why you’re estimating

and not

is always a huge distinction.

If a medical paper compares a regression and a random forest and claims to have “compared machine learning / data science with traditional statistics,” it bothers me, because they have in essence just compared two statistical estimators (or two machine learning estimators).

Similarly, statisticians should consider nonparametric methods like random forests part of nonparametric statistics, rather than dismissing them as “machine learning.”

Past methods might be the future:

We need more attention to the adjustment of lab reference ranges and medication effects for patient covariates. From a medical perspective, I sometimes become concerned that the promise of new data science techniques overshadows these more tried-and-true endeavors.2

You may feel pressured to provide a magic, data-driven tool. Don’t be. The extraction of knowledge is just as important as providing a tool.

The fewer assumptions one makes, the weaker the conclusions. In medical data science and statistics, in alignment with Tukey’s philosophy, it’s often better to make a simple, true conclusion than a complex, false one.

Most estimation methods, even the most advanced, rely on conditional expectations. Expectations are averages, and the average is just one choice – why not the median?

Randomization is a great method. Trials are the gold standard. I would recommend studying trials (which were not covered in my data science curriculum).

Observational data is an interesting research area (see e.g. work by Pearl or Robins). The “no unmeasured confounders assumption” is a formidable adversary. However, routinely collected observational clinical data is plentiful, and sometimes trials are not possible. The analysis of observational data was also not (directly) covered in my data science curriculum.

The philosophy and teaching of data science and statistics:

In statistics, an estimator is often considered to be a window into some underlying truth, whereas in data science, it is often considered to be a compression of the data. Both viewpoints are valuable.

In the data science curriculum, statistics should serve as an overarching framework to describe estimators of all forms, from those in data mining to those in deep learning.

The data science curriculum could use more emphasis on generative processes (described with probability). This is crucial to safe, patient-centered research.

No data-driven method can escape sampling bias or poor-quality data. Bad sample = bad model. Data and design is usually more powerful than methodology. This is similar to the famous “garbage in, garbage out” saying, which is often used when talking about software or algorithms.

In the statistics curriculum, data science topics like random forests and neural networks should be taught as examples of non-parametric estimation.

In the statistics curriculum, there should be more emphasis on terminology and tools from data science when describing data structures, algorithms, and optimization (there is already extensive focus on these three topics, but usually the terminology and tools are different).

Patients first:

In your dataset, find a patient and try to understand their story. It will guide you.3 I remember once, when the data analysis in my thesis was truly testing me, I found a patient and drilled down into their story, and only then did things end up working out.

Study the language of probability and statistical estimation. Then, you can identify a clinical problem, translate it into this language, and build an estimator that extracts pertinent knowledge from the data. This is in contrast to finding a dataset and looking for a clinical problem.

Having a medical problem you are trying to solve as you learn statistics or data science can be a great motivator. It can also keep you grounded.

You do not need medical training to do statistics or data science research in medicine. Everyone is a patient at some point. There is always a need for more research that is based on the patient’s perspective.

Maximizing utility is crucial. For example, as a researcher, think—like you would as a patient—about side effects in addition to survival.

The study of utility maximization in probabilistic/statistical language, which is also known as decision analysis or treatment regimes (see e.g., work by Pauker, Robins, or Murphy), connects medical statistics, data science, robotics, and the essential task of the healthcare provider.

An inclusive approach:

Medical data science and statistics research is hard. We’re in it together. Collaborate with anyone who is interested in your work, whether they be from statistics, data science, computer science, translational science, basic science, other fields, or the healthcare system more broadly—all have unique and valuable perspectives.

- See http://www-stat.wharton.upenn.edu/~steele/Rants/AdviceGS.html ↩︎

- See https://www.fharrell.com/post/hteview/ ↩︎

- This is based on similar advice from Joel Grus, Allen Downey, Cathy O’Neil, or Rachel Schutt—can’t find the exact reference ↩︎

Leave a comment